|

In this issue ONENOTE: Why there isn’t just one OneNote ON SECURITY: The ASR GUI tool is safe Additional articles in the PLUS issue • Get Plus! SILICON: Will you be able to run Windows on an Arm processor? FREEWARE SPOTLIGHT: Pocket Radio Player — a world of radio stations APPLE NEWS: The Apple M2 arrives ON SECURITY: What should you consider sensitive?

ONENOTE Why there isn’t just one OneNote

By Mary Branscombe OneNote started out on Windows, and it’s been a sleeper success — but getting the full set of features has been confusing. OneNote was always intended to be the one place that you put your notes — and all the other information you need to hang on to — “Things to do, important stuff to remember, things to review, and a bunch of stuff you think you might need some day but can’t be sure,” as Chris Pratley put it when describing his original idea for OneNote back in 2000. It’s supremely useful for that.

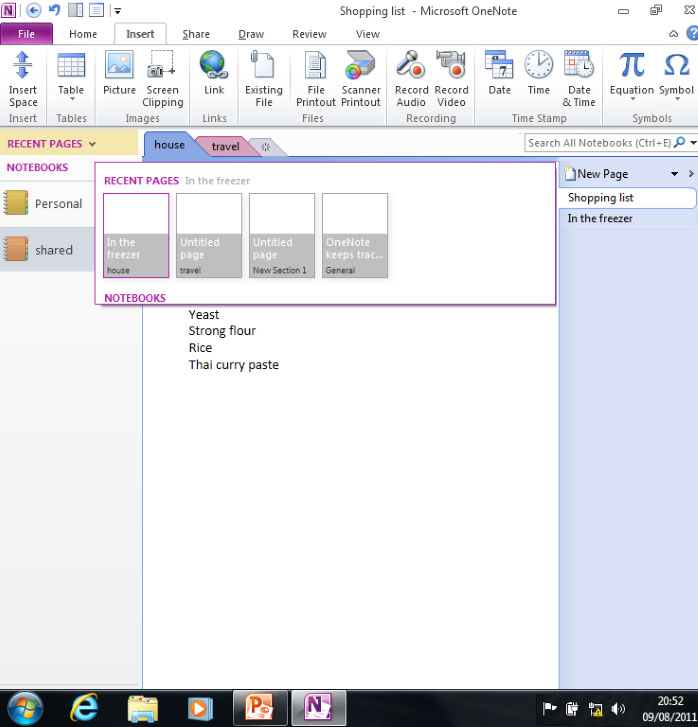

But if you’re going to have one place for all your notes, that place needs to be available on every platform and in every ecosystem, and this leads to a confusing number of ways to get at your notes — from mobile apps to the Web version of OneNote that integrates into Teams. It all began with Windows and the idea that Word wasn’t the right place for everything, especially ephemeral information that wasn’t ready to become a document (and might never become a document). OneNote started out as a desktop Windows application (as you can see in Figure 1) with a lot of inking tools that worked only on the then-new tablet PCs (see Figure 2). Despite being known as “Scribbler” internally, it wasn’t ever intended to be a tablet-only application. The name came about because you could scribble down a note on digital paper without ever stopping to think about where you were supposed to put that kind of information.

The goal? To be great for both inking with a pen and using the keyboard. When it was first revealed as part of the Office 2003 beta 2 release (which anyone could try for the $19.95 cost of postage), Bobby Moore, then product manager for OneNote, said it was good on the desktop for research, better on a laptop for taking notes in meetings, and “best on a tablet PC because of the interactivity and the handwriting recognition.”

But the association with handwritten notes, the marketing budget for tablet PCs, and the way competing apps such as Evernote focused on the tablet market made many people think OneNote was actually just for tablets when it launched in 2003. It didn’t help that the development team initially went down something of a rabbit hole with the first beta, trying to analyze the structure of ink so the app would do magical things as soon as you started writing a list or drawing a diagram. Some of that lives on in the way OneNote lets you click anywhere on the virtual page to start typing — or clip another part of the screen, creating separate chunks of information called note containers. But the powerful features in these early releases were popular: using tags to highlight key information in your notes, enabling audio recordings that automatically synchronized to the notes you typed (when you were recording or playing back), and clipping anything you could see on screen into your notes (see Figure 3).

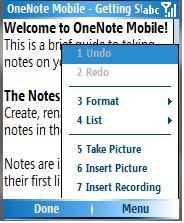

Although the first release of OneNote wasn’t included in any of the Office 2003 packages and thus had to be bought separately, the software slowly became one of Microsoft’s best-hidden successes. OneNote 2003 sold over 100 million copies, and usage tripled with the first service pack. Then usage increased tenfold when Office 2007 included OneNote in both the cheapest and the most expensive bundles (Home and Student at one extreme and the Office Enterprise 2007 and Ultimate 2007 SKUs, along with Groove at the other). You could invite other people into your OneNote notebook and have real-time, peer-to-peer, multiple-user note-taking sessions with OneNote 2003 SP1. OneNote 2007 added shared notebooks that you could sync among multiple PCs and share permanently with colleagues or family members (on a network, over the Web, or by passing around a USB stick) so they could read or add to your notes at any time. When smartphones came along, OneNote 2007 went mobile, using SkyDrive sync to make notebooks available on Windows Mobile (see Figure 4), Pocket PC, and Symbian. SkyDrive, of course, was the forerunner of today’s OneDrive.

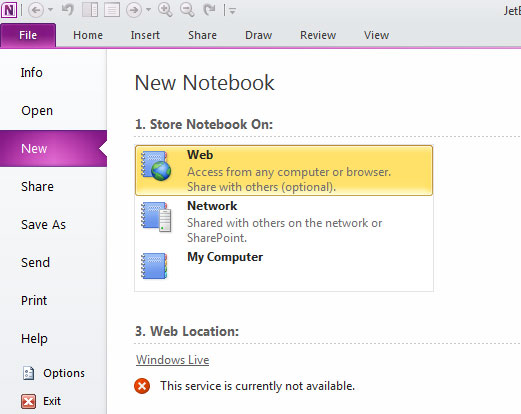

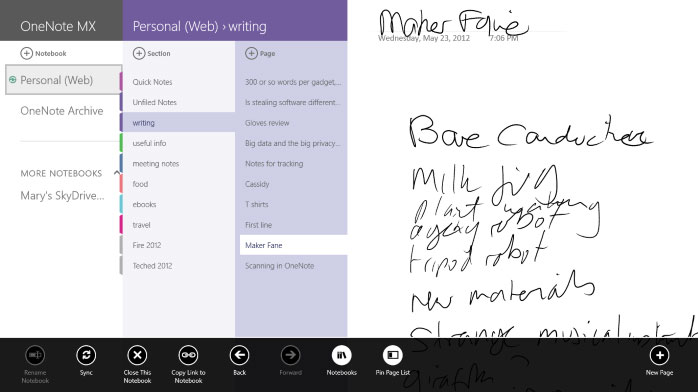

OneNote 2010 made that easier, with the option to save notebooks into SkyDrive (Figure 5). This enabled OneNote for iOS in 2011, for an Android client in 2012 with an initial limit of just 500 notes, and for a Windows RT client called OneNoteMX (Figure 6).

OneNote finally made it into the mainstream SKUs of Office 2013 (see Figure 7). Then, in 2014, Microsoft also created the Mac version users had long been asking for and also made OneNote free for personal use.

Initially, the free version had limited features. You needed to pay for a license if you wanted to record and search audio, password-protect sections, embed files, search handwriting, see page history, or have text in images recognized so you could search for or copy it. By 2015, when the OneNote for Windows 10 app came along (and started getting installed automatically in Windows 10), those features were all free. Paying for OneNote nowadays gets you extra stickers everywhere, a handful of features in the Windows 10 app such as the Math Assistant, the ability to play ink back like a video (handy for teachers), and — on the Windows desktop version only — the ability to store notebooks anywhere you want, not just in OneDrive. That’s an important feature for anyone who has content they’re not comfortable storing in the public cloud. If you want to have a OneNote notebook that lives only on your PC, or on a server, or even on a different cloud-storage service, you need to pay for a Microsoft 365 subscription or a OneNote license — and you can open those notebooks only on Windows, not on a Mac or a smartphone. Meanwhile, Microsoft was busy building a modern storage and sync model that would be more granular and work better for syncing notes from the cloud to lots of different devices. Some details about that project emerged from a job advert posted at the time: Our core Storage Sync model is still based on the original designs from the first version of OneNote. Notes were originally a collection of directories and files on the local drive. Notes are now a collection of directories and files in the cloud with a sync engine and caching placed in between. The current design is limiting, from both the robustness and innovation points of view. OneNote is looking for experts in the fields of cloud storage, databases, sync, authentication, protocols & services to build a modern foundation for all of OneNote’s data. We need a more robust design. We want to enable user sharing and collaboration at a finer level than what is currently possible. We need to support cross platform and devices that have limited local storage and yet still provide access to all of your notes. We need to coordinate with both OneDrive and OneDrive for Business on future Cloud storage designs. We need to account for the millions of existing notebooks being used every day by our millions of users. It’s that tension between supporting the millions of OneNote users’ existing notebooks, and using the shiny new features that this modern cloud sync unlocks, that is behind the years of confusion over the future of OneNote and the Hokey Cokey dance of determining which Windows client users should pick. Although the OneNote for Windows 10 app started as a basic client with the same features on Windows and Windows Phone, the team was busy adding new features (such as tags) that got synced to each new device you used OneNote on — something OneNote users had been asking for since the first version of the software — as well as the modern sync engine. The team was so busy that the desktop version of OneNote got no new features at all in Office 2016, apart from an update to match the Office interface (see Figure 8). In fact, OneNote 2016 didn’t even get new Office features such as Tell Me (the search tool for Office features, developed from Ribbon Hero — created by Chris Pratley’s new team in Office Labs), let alone long-requested features such as a word count.

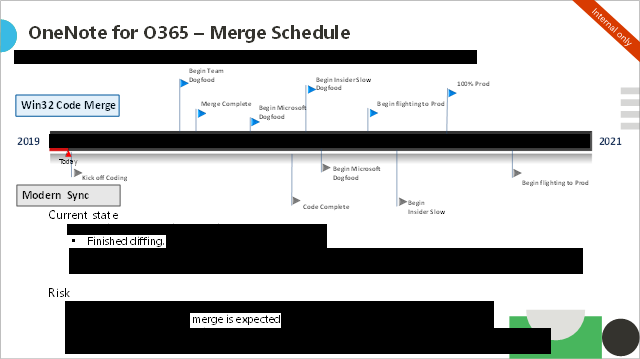

When Office 2019 came along in 2018, Microsoft started aggressively updating users to the 64-bit version of Office by uninstalling and reinstalling applications. Not only was there no OneNote 2019, but some of the OneNote extensions that users relied on for features such as word count, macros, image cropping, reminders, and a calendar view of your notes didn’t have 64-bit versions at the time. Perhaps because of that, Office 2019 often didn’t reinstall OneNote 2016 (which would still have lost any customizations such as custom tags, which even now don’t sync between devices). Instead, Microsoft replaced it with OneNote for Windows 10 and began referring to desktop OneNote as the “legacy” version. Even more frustration was caused by the standalone version of OneNote 2016 that Microsoft made available for download using the Click-to-Run installer (used by Office 365 and volume-licensed versions of Office 2019). The C2R installer is incompatible with versions of Office installed by MSI, and OneNote 2016 is not available through the Microsoft Store. It sounded like something of a concession when Microsoft announced it was extending mainstream support for OneNote 2016 to match the rest of Office 2019 and was once again installing it with the rest of Office. But at Ignite 2019, the OneNote team made a more ambitious promise when OneNote Principal Product Manager Ben Hodes announced that the team was “merging all of our modern code back into the legacy [OneNote] 2016 codebase to create a unified, single code base from which we can ship and deliver OneNote.” (See Figure 9.)

Two versions of OneNote on Windows, with broadly the same features, would be shipped. “There may be something where one [Windows client] gets it before the other, but in general our goal is that everybody gets a new feature as we develop it,” Hodes said at the time, noting that “we love OneNote for Windows 10” and that many members of the OneNote team used it themselves. That meant that OneNote for Windows 10 would get new Office features such as Loop and @ mentions as soon as they came to OneNote 2016 — as well as existing OneNote 2016 features such as AutoCorrect and support for add-ins). Desktop OneNote, by contrast, would get the app features such as dark mode, playing back ink that you’d written stroke by stroke, and the modern sync engine — including syncing custom tags. And both Windows OneNote clients would get new features such as the ability to share just a section of a notebook and read-only sections, popular features that were already in the education versions of OneNote. Having the merged codebase would free up the OneNote team to bring more features from Office — such as multilingual support, advanced data-leak protection, and the ink features in Office that had leapfrogged some OneNote ink options. It sounded like the best of both worlds, and a few features (such as dark mode in the desktop app) arrived very quickly. But it would also be a lot of work, Hodes warned up front. Would merging two very different codebases really work? It would take a couple of years to find out …

Mary Branscombe has been a technology journalist for nearly three decades, writing for a wide range of publications. She’s been using OneNote since the very first beta was announced — when, in her enthusiasm, she trapped the creator of the software in a corner.

ON SECURITY The ASR GUI tool is safe

By Susan Bradley Most antivirus programs flag ASR GUI as infected. Those results are false positives. In my most recent AskWoody MS-DEFCON Alert, I recommended a tool to help you set preventive attack rules, otherwise known as ASR (Attack Surface Reduction) rules. I’ve recommended ASR GUI tool for years because Microsoft doesn’t provide an easy GUI to set rules for standalone computers. As was quickly pointed out in our forums and in emails we’ve received from readers, many antivirus programs flag the tool as dangerous. A notable exception is Microsoft Defender, which understands the underlying cause and knows it isn’t dangerous. What is the cause? As I confirmed recently, the root cause is that ASR GUI uses Microsoft’s own PsExec2 software, which is a lightweight telnet replacement. The problem is that PsExec2 is used (or abused) by many attackers in their malware, so they use PsExec2 as a marker that the scanned program is dangerous. As Microsoft notes on the download page for PsExec2: … some anti-virus scanners report that one or more of the tools are infected with a “remote admin” virus. None of the PsTools contain viruses, but they have been used by viruses, which is why they trigger virus notifications. It’s true that you can use registry methods to deal with the zero day described in the recent Alert. However, using the GUI to set ASR rules that block child processes is a better solution and I continue to recommend it. For those in businesses, you can use other tools, such as as Group Policy and Intune, to set ASR rules. I will have more to say about false positives in an upcoming column.

Susan Bradley is the publisher of the AskWoody newsletters.

The AskWoody Newsletters are published by AskWoody Tech LLC, Fresno, CA USA.

Your subscription:

Microsoft and Windows are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. AskWoody, AskWoody.com, Windows Secrets Newsletter, WindowsSecrets.com, WinFind, Windows Gizmos, Security Baseline, Perimeter Scan, Wacky Web Week, the Windows Secrets Logo Design (W, S or road, and Star), and the slogan Everything Microsoft Forgot to Mention all are trademarks and service marks of AskWoody Tech LLC. All other marks are the trademarks or service marks of their respective owners. Copyright ©2022 AskWoody Tech LLC. All rights reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||